The discussion about a reliable, economical and at the same time climate-conscious energy supply is becoming increasingly differentiated. In addition to heat pumps, photovoltaics and storage systems, the focus is shifting to technologies that generate electricity and heat at the same time, thereby minimising losses.

Combined heat and power plants have been among these solutions for years, but are often underestimated or prematurely classified as transitional technologies. However, it is precisely in combination with other generators that the potential of this form of combined heat and power becomes apparent.

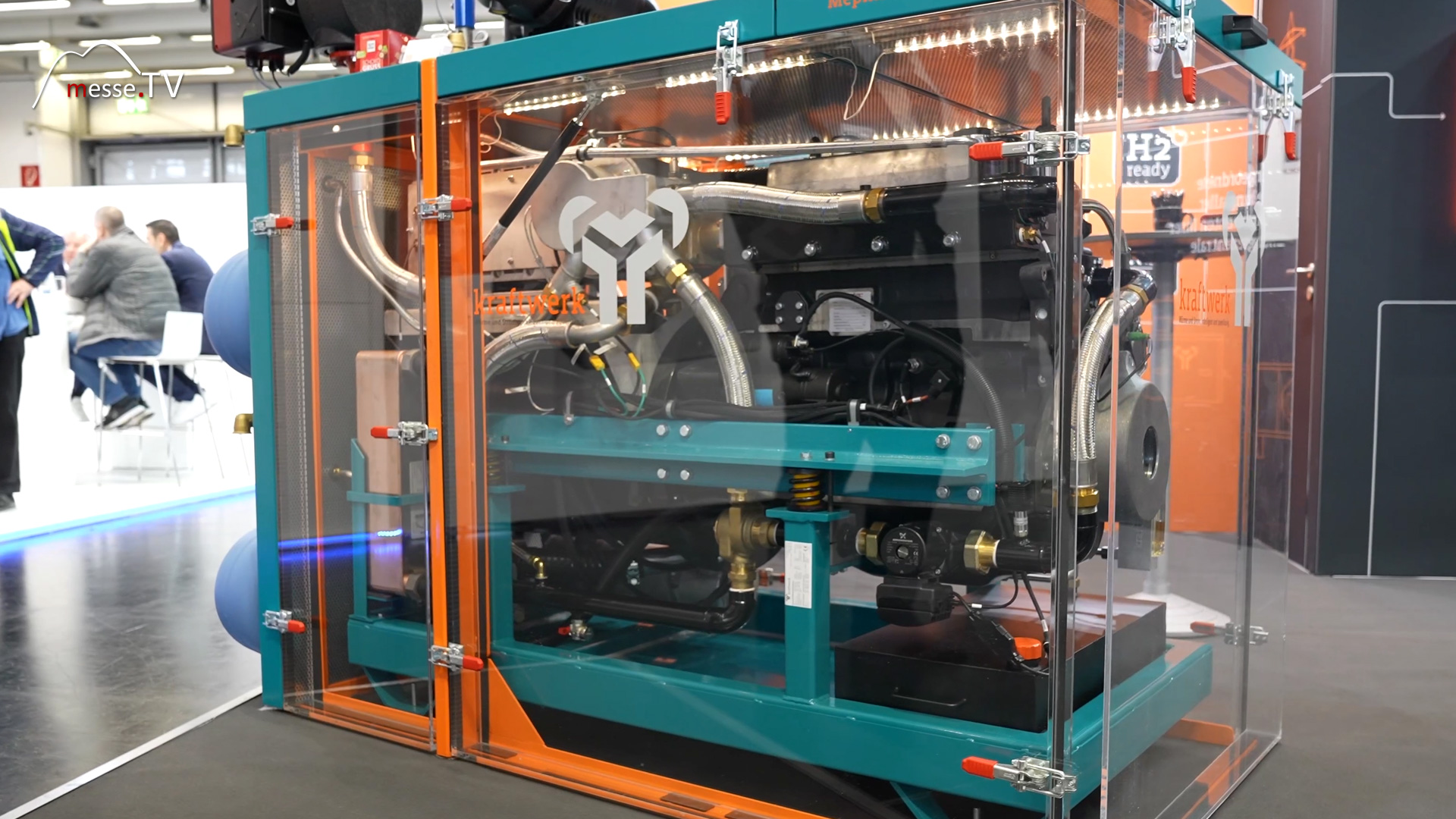

The manufacturer, headquartered in Hanover, specialises in combined heat and power plants with an output range of approximately eight to fifty kilowatts of electricity. The company therefore does not target large industrial plants, but rather the typical needs of apartment buildings, commercial properties, municipal facilities and larger single-family homes. With several thousand systems installed, the technology is well established throughout Germany and has long since outgrown its niche status. The claim goes beyond the individual unit. Combined heat and power plants are not viewed in isolation, but as part of an overall system that links various energy sources. This approach is becoming increasingly important, particularly in the context of sector coupling.

A central idea is the combination of a combined heat and power plant and a heat pump. While the combined heat and power plant generates electricity and usable heat, the self-produced electricity can be used directly to operate the heat pump. This creates synergies that improve both economic efficiency and energy efficiency. This interaction is complemented by a higher-level control system that coordinates all generators in the boiler room. Photovoltaics, combined heat and power plants, grid electricity and, if necessary, battery storage are brought together in one system. The control system decides which energy source to use and how to make optimum use of electricity and heat depending on the situation.

The operating principle of a combined heat and power plant is relatively simple and therefore robust. At its heart is a gas-powered combustion engine. This drives a generator that produces electricity. The waste heat generated during combustion is not simply dissipated, but is made available for heating and hot water via heat exchangers. Various types of gas are used, including natural gas and biogas. The plants are certified accordingly and designed for flexible operation. The electricity generated can be used directly in the building or, depending on the design, fed entirely into the public grid.

The great advantage of this technology lies in its overall efficiency. While conventional large-scale power plants lose a considerable portion of the energy they use as waste heat, combined heat and power plants utilise almost all of the energy. A single unit of gas is used to simultaneously generate electricity and heat, which are used on site. As a result, efficiency levels are achieved that are significantly higher than those of conventional power generation. Compared to centralised power stations in particular, it becomes clear how efficient the decentralised use of fuels can be. The approach here is not to sacrifice efficiency at any cost, but to use existing energy sources with as little loss as possible.

In addition to efficiency, cost-effectiveness is a key factor for operators. Combined heat and power plants are particularly advantageous in locations where there is a consistent demand for heat throughout the year. In such cases, the plant can achieve long operating times, which makes the investment worthwhile. Typical areas of application are:

At first glance, the use of gas-powered technology seems contradictory in the context of climate protection. However, when viewed in the overall context, a more nuanced picture emerges. The decisive factor is the comparison with conventional power generation. If gas is used decentrally with high efficiency, emissions can be reduced as a result. The approach follows the principle of generating energy where it is needed, rather than accepting losses due to transport and conversion. In combination with biogas or, in the future, renewable gases, this effect can be further enhanced.

The strength of modern combined heat and power plants increasingly lies in their integration into complex energy systems. Intelligent control systems can be used to cushion peak loads, increase self-consumption rates and flexibly combine different generators. In combination with photovoltaics in particular, this creates a system that combines electricity generation and heat supply in line with demand. This technology is also suitable for neighbourhood solutions or smaller local heating networks. Here, several buildings can be supplied by a central plant without sacrificing the efficiency advantages of combined heat and power.

Combined heat and power plants are an example of a pragmatic approach to the energy transition. Instead of relying exclusively on large-scale centralised structures, the focus is shifting to the decentralised, efficient use of energy. Electricity and heat are generated together, used directly and controlled intelligently. This makes it clear that combined heat and power plants are more than just a bridging technology. In well-planned systems, they can make a stable, economical and efficient contribution to energy supply, especially where continuous heat demand meets flexible electricity use.